Building The Blanding Consultant

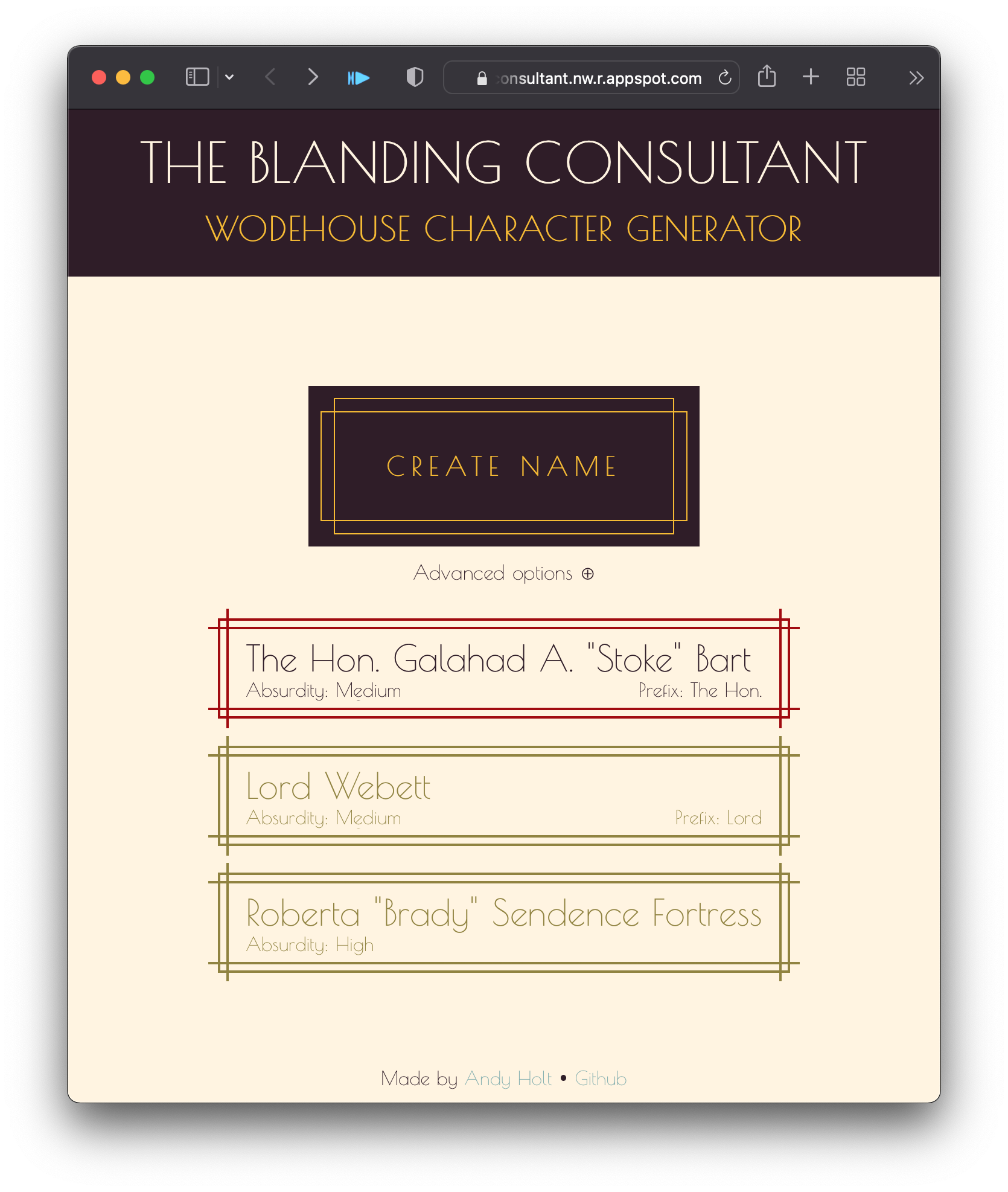

The Blanding Consultant is an AI1 character name generator, producing P. G. Wodehouse style character names. These generated character names can be used just for fun, or as a prompt for creative writing or improvisation.

P. G. Wodehouse2 (1881–1975) was an English humourist and writer, known for his stories set among the upper classes of early 20th century English society. He is the master of the gentle but hilarious story, with delightfully interwoven plot lines, unforgettable characters, and arresting turns of phrase: "He looked like a sheep with a secret sorrow." Probably his two best known series are Jeeves and Wooster and Blandings. The name of my character name generator is a reference to Blandings, the castle home of Lord Emsworth and his prize pig, Empress. Its also a play on being a branding consultant – very clever, but perhaps not quite Wodehousian.

In this post, I will detail the process of building The Blanding Consultant.

Generating the names

New character names are generated by a recurrent neural network, using TensorFlow in Python. To train the network, I first needed a list of the character names in Wodehouse stories. Thankfully Wikipedia has a page dedicated to just such a list, which needed just a little tidying up and normalising to provide a training data set:

"Battling" Billson "Gazeka" Firby-Smith "Puffy" Benger "Smooth" Sam Fisher "Spennie", Earl of Dreever Adair Admiral George J. "Fruity" Biffen Agatha Gregson, Lady Worplesdon Agnes Flack ...

Unfortunately, though Wodehouse was prolific as an author, the number of characters across all his stories is rather limited: I got 415 in my training set. Generally we need at least tens of thousands, ideally hundreds of thousands of examples to train a good machine learning model, so a few hundred character names is clearly insufficient. A workaround is to start with a neutral network which has been trained on general English language data, and tune this with a final stage of training on the limited data set we want to emulate. The textgenrnn project provides exactly such a model, which can be easily retuned to the Wodehouse character name training set. The project hasn't been updated for a few years, so it took a little bit of debugging to get it running with the latest versions of TensorFlow and Keras, but once running, it performed remarkably well.

The next issue was to get the level of tuning to the character name data right: too little, and the model would simply produce general English, not distinctively Wodehousian names. But too much, and the model would become overfitted, and simply reproduce actual characters, being unable to produce similar, but distinctive, character names. I found that ten epochs got the right balance, and was reliability producing original, but recognisably Wodehousian, characters.

from textgenrnn import textgenrnn

textgen = textgenrnn()

textgen.train_from_file('wodehouse-characters-su.txt', num_epochs=10)One the model was trained, the next stage was to turn this model into a web app, with an API to return a character name when requested. I built this using Flask, since the machine learning was being done in Python anyway. This is one of the joys of using Python as a programming language: its easy to cross from one field into another, using specialised and mature packages.

I added some extended functionality to the name generator, to allow the user to adjust the "absurdity" of the names given. This absurdity measure translates into the "temperature" of the neural network generation. A low value means more safer samples generated, at the cost of being more likely to replicate actual character names instead of generating new ones. A higher absurdity means more risky character name generation: more original, but at the cost of being more likely to be nonsense.

Another extended feature is the ability to provide a "prefix" for the generator, a letter, title, name which becomes the start of the generated name. This allows a user to generate a particular kind of name, should they need a more specific character. For example, one can provide a male or female name to produce a specifically gendered character, or a title to create a Lord, a Lady, or some other appropriate aristocrat.

Building the frontend

With the backend working, my attention turned to the frontend. It was all very well to have a flask app running well, responding to URL requests with JSON data. But that's not very user friendly. It also gave me the opportunity to learn React. Other than the initial learning curve of learning React, and frontend development in general, I found building in React straightforward and an enjoyable process.

The biggest hurdle in developing The Blanding Consultant app was how to hook up

the frontend React app to the backend api provided by Flask. Many forum and blog

posts suggested that this would require the useEffect hook. However, the nature

of the app is that the API data only updates when requested by clicking the

"Create Name" button. Instead, the app can simply make a request using fetch() as

part of handling the button click, and use this to update state, in a .then

handler.

The final stage of building the frontend was the aesthetic. The Blandings novels, like most of Wodehouse, are set in an English stately home of the early 20th century, so an art deco theme seemed appropriate, but I also wanted it to be clean and simple – after all, Lord Emsworth is no Gatsby.

Deployment

Once the frontend was running locally and interacting with the backend API, the final step was deployment, so as to be a real life web app. I chose to use Google Cloud for deployment, mainly because I wanted to learn how to use Google Cloud, and it offers very flexible hosting options.

I decided to run the backend and the frontend as two separate web apps, running each as an independent service, providing maximum modularity, and allowing moving of either part to a different service or hosting arrangement if desired.

Getting the backend running on Google Cloud App Engine was more difficult than anticipated. The gunicorn server would start up and begin initialising, but then the process would be killed before a request could receive a response. Debugging in GCloud was challenging, as there did not seem to be a straightforward way to get debugging information from the server. After several hours of fruitless debugging, I managed to access enough of an error message (by copy-pasting an error message from the GCloud dashboard into a text editor) to find that the process was being killed by the supervisor because of high memory usage.

Since the app was taking up too much memory, this led me to look closely at the

memory usage, and I discovered a memory leak. This was difficult to diagnose,

because it appeared not to be a single object taking up lots of memory

(tracemalloc therefore did not help), but many, many small objects each using a

small amount of memory, building up. The solution was to use keras to clean up

in between each name generation:

tf.keras.backend.clear_session()

gc.collect()Even with this memory leak fixed, the memory usage was still too high to run in GCloud's base F1 instance. Deploying to an F2 instance gave enough memory overhead to run the app without problems. The warm up time of the RNN is significant, so I have tried to configure GCloud to have a process running and ready to respond, even when things have been quiet for some time.

Deploying the frontend was much simpler by comparison, no doubt in part because I had learned to use GCloud and the appropriate tools and services while dealing with the backend deployment.

The most useful next step of development would probably be to try to get the

name generating neural network to run with a smaller memory footprint. This

would not be simple, however, as this would require jettisoning the textgenrnn

package. It would be a good exercise to use TensorFlow directly for the neural

net, but this will reintroduce the problem of having an intrinsically small

training data set.

This was an interesting project, giving me the opportunity to develop my full-stack web development skills. The Blanding Consultant is available online here.

I prefer the term "machine learning". This is not just pedantry and personal choice. The term machine learning is more precise and, I would argue, more accurate. While AI has a specific definition within the CS field (as a superset of ML), this is generally not understood when AI is spoken of colloquially and within political and media discussions. So I use the term for its attention grabbing value here, but will use "machine learning" from now on.

Pronounced Wood-house. I don't know why its spelt that way either.